Logical Vectors, Bayesian power analyses, and ROPEs

Phil Chalmers

February 20, 2026

Source:vignettes/SpowerIntro_logicals.Rmd

SpowerIntro_logicals.RmdLogical returns

In many applications it can be advantageous to directly return

logical values in the simulation experiment rather than

letting Spower() perform these threshold transformations

internally (e.g., using sig.level) as these can include

more intricate experimental requirements. The following showcases

various ways that returning logical values works in the

Spower package, where the average across the collected

TRUE/FALSE values reflects the target power

estimate.

Note that returning a logical in the simulation

experiment necessarily implies that the sig.level argument

in Spower() and friends will not be used, and therefore

suitable alternatives must be defined within the context of the

simulation experiment code (e.g., including conf.level or

sig.level in the simulation experiment function

directly).

Confidence (and credible) intervals

Keeping with the basic -test experiment in the introduction vignette, suppose we’re interested in the power to reject the null hypothesis in a one-sample -test, where is the probability of the observing the data given the null hypothesis. Normally, one could simply write an experiment that returns a -value in this context, such as the following,

However, an equivalent way to explore power in this context would be to investigate the same null hypothesis via confidence intervals given a specific level to define their range, where .

If one were to take this approach, the defined simulation function

should return a logical value based on the relation of the

parameter estimate to the CI, where the CI is used to evaluate the

plausibility of

.

Specifically, in the context of using CI’s to reflect

-value

logic, the CI is used to evaluate whether

falls outside the advertised interval, returning

TRUE if outside the CI and FALSE if within the

interval. Alternatively, if one were in a Bayesian analysis context, a

credible interval could be used instead of the confidence

interval to construct the same logical output.

The following code demonstrates this logic, assuming that

(and therefore a two-tailed, 95% CI is used), and uses the

is.outside_CI() function to evaluate whether the

parameter falls outside the estimated CI returned from

t.test().

l_single.t <- function(n, mean, mu=0, conf.level=.95){

g <- rnorm(n, mean=mean)

out <- t.test(g, mu=mu, conf.level=conf.level)

CI <- out$conf.int

is.outside_CI(mu, CI) # equivalent to: !(CI[1] < mu && mu < CI[2])

}

l_single.t(100, mean=.2)## [1] TRUEEvaluating the power analysis with Spower() works out of

the box now, noting again that l_single.t() will ignore the

Spower(..., sig.level) information altogether as it is no

longer relevant when logical information is returned. The

following compares both the

-value

and logical CI approaches, both of which provide identical inferential

information in this case (this will not always be true; the

-test

simply reflects a special case).

p_single.t(n=100, mean=.3) |> Spower()##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:00:03

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## n mean sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 100 0.3 0.05 NA

##

## Estimate of power: 0.846

## 95% Confidence Interval: [0.839, 0.853]

l_single.t(n=100, mean=.3) |> Spower()##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:00:04

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## n mean sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 100 0.3 0.05 NA

##

## Estimate of power: 0.841

## 95% Confidence Interval: [0.834, 0.849]Using previouls defined simulation code

Note that even in the CI context presented above, writing

user-defined functions may not be entirely necessary. This is because

the related, internally defined function p_t.test() can be

used to obtain the same CI information by returning the model itself,

and subsequently extracting the $conf.int element. The

benefit of this, as shown below, is that users do not need to reinvent

the data generation and analysis portions of the experiment if this is

already available in the package.

l_single.t <- function(n, mean, mu=0, conf.level=.95){

# return analysis output from t.test() for further extraction

out <- p_t.test(n=n, d=mean, mu=mu, type='one.sample',

conf.level=conf.level, return_analysis=TRUE)

CI <- out$conf.int

is.outside_CI(mu, CI)

}

l_single.t(100, mean=.2)## [1] FALSEPrecision criterion

Using confidence or credible intervals are also useful in contexts where specific precision criteria are important to satisfy. Suppose that, in addition to detecting a particular effect of interest in a given sample, the results are only deemed “practically useful” if the resulting effect size inferences are sufficiently precise, where precision could be based on the magnitude of the SE, the width of the uncertainty interval, or other relevant precision-based criterion. In this case, one may join the logic of the -value/CI approaches to create a joint evaluation for power, where a result is deemed both “significant and useful” if the null hypothesis is significantly rejected and the CI is sufficiently narrow.

As a working example, suppose that the above one-sample -test experiment was generalized such that a meaningfully significant result would require a) the rejection of the null, , and b) a CI width less than 1/4 standardized mean units. What value of would be required to obtain such a significant and sufficiently accurate inference to obtain a power of 80% given, say, the “small” effect size of ?

l_precision <- function(n, mean, CI.width, mu=0, alpha=.05){

g <- rnorm(n, mean=mean)

out <- t.test(g, mu=mu)

CI <- out$conf.int

width <- CI[2] - CI[1]

# return TRUE if significant and CI is sufficiently narrow

out$p.value < alpha && width < CI.width

}

l_precision(n=interval(10, 500), mean=.2, CI.width=1/4) |>

Spower(power=.80)

# equivalently:

# l_precision(n=NA, mean=.2, CI.width=1/4) |>

# Spower(power=.80, interval=c(10, 500))##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:00:22

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## n mean sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 NA 0.2 0.05 0.8

##

## Estimate of n: 272.6

## 95% Predicted Confidence Interval: [272.0, 273.2]Compared to the required

from a power analysis that just contains a significant result, this

joint practical significance criteria requires a meaningfully higher

sample size. Note that in the special case where

CI.width=Inf then all CI widths will be accepted, which

will result in the same power output that would have been obtained using

p_single.t().

##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:00:20

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 5

## n mean CI.width sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 NA 0.2 Inf 0.05 0.8

##

## Estimate of n: 198.8

## 95% Predicted Confidence Interval: [197.2, 200.2]Bayes Factors

If one were using a Bayesian analysis criteria rather than the

-value

approach, the Bayes factor

()

ratio could be used in the logical return context too. For

example, returning whether the observed

in a given random sample would indicate at least “moderate” supporting

evidence for the hypothesis of interest compared to some competing

hypothesis (often the complementary null,

,

though not necessarily), and the average across the independent samples

would indicate the degree of power when using this Bayes factor

cut-off.

The downside of focusing on BFs is that they require the computation

of the marginal likelihoods, typically via bridge sampling (e.g., via

the bridgesampling package), in addition to fitting the

model using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods (e.g.,

brms, rstan, rstanarm). Though

not a strict limitation per se, it is often more natural to focus

directly on the sample from posterior distribution for power analysis

applications rather than on the marginal Bayes factors; this is

demonstrated in the next section. Nevertheless, such applications are

possible with Spower if there is sufficient interest in

doing so.

As a simple example, the following one-sample

-test,

initially defined above, could be redefined to focus on output from the

BayesFactor package, which returns the

criteria in log units (hence, exp() is used to return the

ratio to its original metric) assuming a non-informative Jeffreys prior

for

.

In this case a TRUE is returned if the Bayes factor is

greater than 3 and FALSE if less than or equal to 3.

Finally, to ensure that nothing important is lost in the simulation

experiment code a data.frame() object is returned instead

of just the logical information, while

Spower() is informed to only focus on the

logical information for the purpose of the power

computations.

l_single.Bayes.t_BF <- function(n, mean, mu=0, bf.cut=3){

g <- rnorm(n, mean=mean)

res <- BayesFactor::ttestBF(g, mu=mu)

bf <- exp(as.numeric(res@bayesFactor[1])) # Bayes factor

data.frame(largeBF=bf > bf.cut, bf=bf)

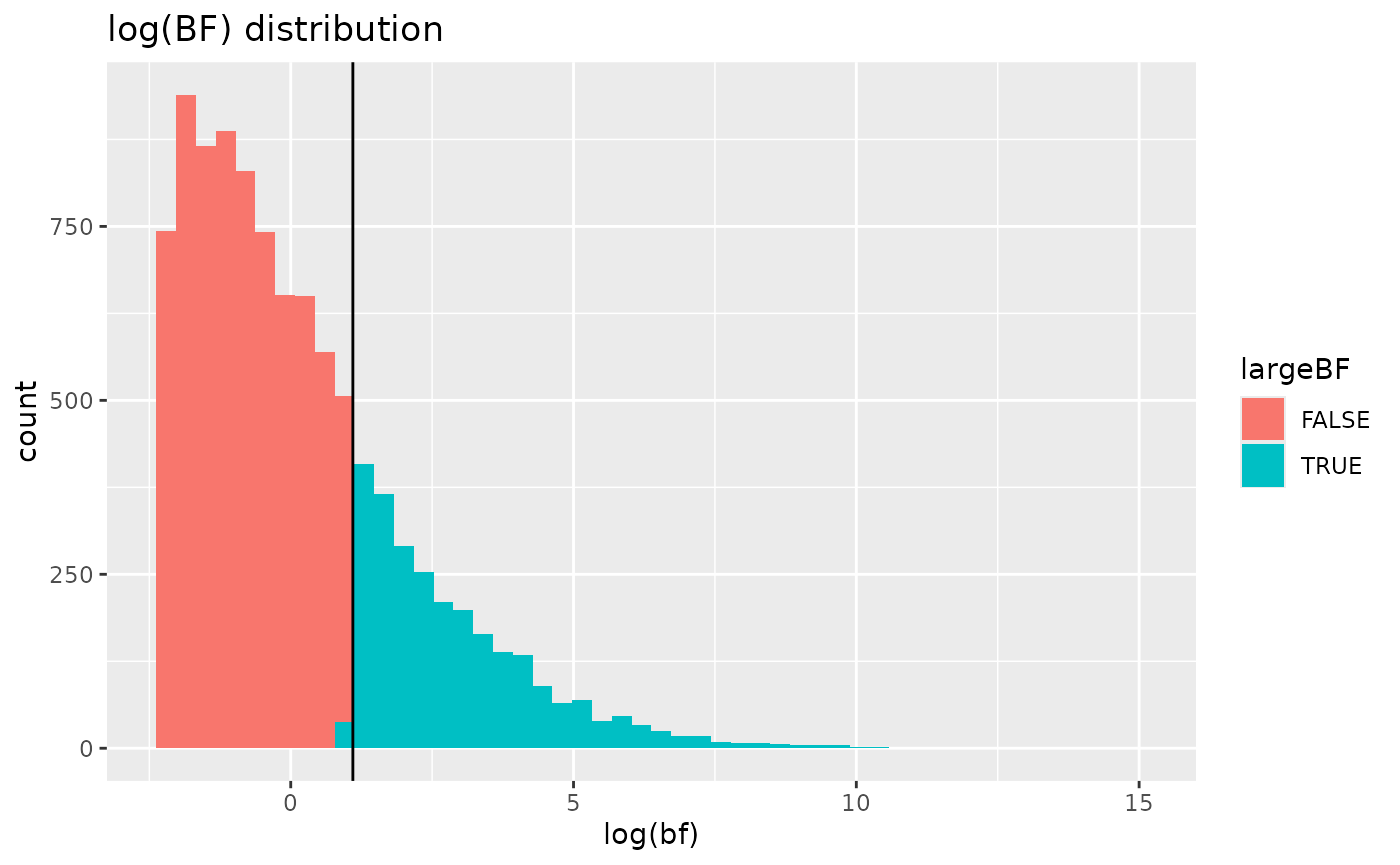

}Evaluating this simulation with , , and gives the following power estimate.

l_single.Bayes.t_BF(n=100, mean=.5, mu=.3) |> Spower(select='largeBF') -> BFsim

BFsim##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:01:24

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 5

## n mean mu sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 NA

##

## Estimate of power: 0.265

## 95% Confidence Interval: [0.257, 0.274]To view the complete simulation results use SimResults()

on the resulting output, which if useful could be further plotted. Note

that when plotting Bayes factors it is advantageous to present the plot

in natural log units.

BFresults <- SimResults(BFsim)

BFresults## # A tibble: 10,000 × 6

## n mean mu sig.level largeBF bf

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl> <dbl>

## 1 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 FALSE 0.131

## 2 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 FALSE 1.04

## 3 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 FALSE 2.73

## 4 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 TRUE 43.4

## 5 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 FALSE 0.168

## 6 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 FALSE 1.06

## 7 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 TRUE 3.73

## 8 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 TRUE 442.

## 9 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 TRUE 11.3

## 10 100 0.5 0.3 0.05 TRUE 4.11

## # ℹ 9,990 more rows

# use log-scale for Bayes factors as this is a more useful metric

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(BFresults, aes(log(bf), fill=largeBF)) +

geom_histogram(bins=50) + geom_vline(xintercept=log(3)) +

ggtitle('log(BF) distribution')

Bayesian power analysis via posterior probabiltes

The canonical way that Spower has been designed focuses

primarily on

-values

involving the null hypothesis to be tested

().

The reason for setting the package up this way is so that the parameter

(sig.level) can be used as the “line-in-the-sand” threshold

to flag whether a null hypothesis was rejected in each sample of data as

this behaviour is common among popular power analysis software. Bayesian

power analysis, on the other hand, are also supported by the package,

where instead the posterior probability of the alternative hypothesis,

,

is the focus of the simulation experiment.

Continuing with the simple one-sample

-test

example in the introduction vignette and above, were the power analysis

context be that of a Bayesian analysis the conditional probability of

the alternative,

,

may be used instead. For this to work with Spower though, the

argument sig.direction = 'above' should be supplied, where

now the sig.level indicates that “significance” only occurs

when an probability observation is above the define

sig.level cutoff (hence, the default of .05 is

no longer reasonable and should be modified).

Below is one such Bayesian approach using posterior probabilities

using the BayesFactor package, which is obtained by

translating the Bayes factor output into a suitable posterior

probability and focusing on the alternative hypothesis (hence, the

posterior probability returned corresponds to

).

The following also assumes that the competing hypotheses are equally

likely when obtaining the posterior probability (hence, prior odds are

1:1, reflected in the argument prior_odds).

# assuming P(H1)/P(H0) are equally likely; hence, prior_odds = 1

pp_single.Bayes.t <- function(n, mean, mu, prior_odds = 1){

g <- rnorm(n, mean=mean)

res <- BayesFactor::ttestBF(g, mu=mu)

bf <- exp(as.numeric(res@bayesFactor[1])) # Bayes factor

posterior_odds <- bf * prior_odds

posterior <- posterior_odds / (posterior_odds + 1)

posterior # P(H_1|D)

}For the Bayesian

-test

definition in the next code chunk evaluation, “significance” is obtained

whenever the sample posterior is greater than

sig.level = .90, demonstrating strong support of

.

Note that this is a more strict criteria than the null hypothesis

criteria presented in the introduction vignette, and therefore has

notably lower power.

# power cut-off for a significantly supportive posterior is > 0.90

pp_single.Bayes.t(n=100, mean=.5, mu=.3) |>

Spower(sig.level = .90, sig.direction = 'above')##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:01:23

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 5

## n mean mu sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 100 0.5 0.3 0.9 NA

##

## Estimate of power: 0.150

## 95% Confidence Interval: [0.143, 0.157]With this approach all of the power analysis criteria described in

help(Spower) are still possible, where for instance solving

other experimental components (such as the sample size n)

are easy to setup by providing suitable NA argument flags

and search intervals in Spower().

Regions of practical equivalence (ROPEs)

This section presents two related concepts for estimating the power where some justifiable equivalence interval is of interest.

Equivalence testing

As an alternative approach to the rejection of the null hypothesis via the -value or CI approaches, there may be interest in evaluating power in the context of establishing equivalence, or in directional cases superiority or non-inferiority. The purpose of an equivalence tests is to establish that, although true differences may exist between groups, the differences are small enough to be considered “practically equivalent” in all subsequent applications.

As a running example, suppose that in an independent samples -test the two groups might be considered “equivalent” if the true mean difference in the population is somewhere above but below , where the s are used to define the equivalence interval. If, for instance, two groups are to be deemed statistically equivalent given these boundary locations then, using a two-one sided hypothesis testing approach (TOST), the two null hypotheses must be evaluated are and Rejecting both of these null hypotheses leads to the induced complementary hypothesis of interest or in words, the population mean difference falls within the defined region of equivalence. Superiority testing and non-inferiority testing follow the same type of logic, however rather than defining a region of equivalence only one tail of the equivalence interval is of interest.

To put numbers to the above expression, suppose that the true mean

difference between the groups was

(labeled delta), and each group had an

(labeled sds). Furthermore, suppose any true

difference that fell within the equivalence interval

(labeled equiv) would be deemed practically equivalent a

priori. The power to jointly reject the above null hypotheses, and

therefore conclude the groups are practically equivalence

(),

is evaluated in the following output for an experiment with

observations

(

for each group).

l_equiv.t <- function(n, delta, equiv, sds = c(1,1),

sig.level = .025){

g1 <- rnorm(n, mean=0, sd=sds[1])

g2 <- rnorm(n, mean=delta, sd=sds[2])

outL <- t.test(g2, g1, mu=-equiv[1], alternative = "less")$p.value

outU <- t.test(g2, g1, mu=equiv[2], alternative = "less")$p.value

outL < sig.level && outU < sig.level

}##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:00:06

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## n delta sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 50 1 0.05 NA

##

## Estimate of power: 0.844

## 95% Confidence Interval: [0.837, 0.851]In this case, the power to conclude that the two groups are

equivalent, expressed as a percentage, is 84%. You can verify that these

computations are correct by comparing to established software for now,

such as via the TOSTER package.

TOSTER::power_t_TOST(n = 50,

delta = 1,

sd = 2.5,

eqb = 2.5,

alpha = .025,

power = NULL,

type = "two.sample") Two-sample TOST power calculation

power = 0.8438747

beta = 0.1561253

alpha = 0.025

n = 50

delta = 1

sd = 2.5

bounds = -2.5, 2.5

NOTE: n is number in *each* groupAgain, the same type of logic can be evaluated using CIs

alone, and with the built-in p_t.test() function, where in

this case TRUE is returned if the estimated 90%

CI falls within the defined equivalence interval.

l_equiv.t_CI <- function(n, delta, equiv,

sds = c(1,1), conf.level = .95){

out <- p_t.test(n, delta, sds=sds, conf.level=conf.level,

return_analysis=TRUE)

is.CI_within(out$conf.int, interval=equiv) # returns TRUE if CI is within equiv interval

}

# an equivalent power analysis for "equivalence tests" via CI evaluations

l_equiv.t_CI(50, delta=1, equiv=c(-2.5, 2.5),

sds=c(2.5, 2.5)) |> Spower()##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:00:05

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 4

## n delta sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 50 1 0.05 NA

##

## Estimate of power: 0.851

## 95% Confidence Interval: [0.844, 0.858]Bayesian approach to ROPEs (HDI + ROPE)

Finally, though not exhaustively, one could approach the topic of

practical equivalence using Bayesian methods using draws from the

posterior distribution of interest, such as those available from BUGS or

HMC samplers (e.g., stan). This approach is highly similar

to the equivalence testing approach described above, but uses highest

density interval + ROPE in Bayesian modeling instead. Below is one such

example that constructs a simple linear regression model with a binary

term that is analysed with rstanarm::stan_glm().

library(bayestestR)

library(rstanarm)

rope.lm <- function(n, beta0, beta1, range, sigma=1, ...){

# generate data

x <- matrix(rep(0:1, each=n))

y <- beta0 + beta1 * x + rnorm(nrow(x), sd=sigma)

dat <- data.frame(y, x)

# run model, but tell stan_glm() to use its indoor voice

model <- quiet(rstanarm::stan_glm(y ~ x, data = dat))

rope <- bayestestR::rope(model, ci=1, range=range, parameters="x")

as.numeric(rope)

}In the above example, the proportion of the sampled posterior

distribution that falls within the ROPE is returned, which works well

with the sig.level argument coupled with

sig.direction = 'above') in Spower() to define

a suitable accept/reject cut-off. Specifically, if

sig.level = .95 and sig.direction = 'above')

then the ROPE will only be accepted when the percentage of the posterior

distribution that falls within the defined ROPE is greater than .95.

This can of course be performed manually, returning a TRUE

when satisfied and FALSE otherwise, however in this case it

is not necessary.

Below reports a power estimate given

,

where the ROPE criteria is deemed satisfied/significant if 95% of the

posterior distribution for the

falls within the defined range of

.

Due to the slower execution speeds of the simulations the power

evaluations are computed using parallel=TRUE to utilize all

available cores.

rope.lm(n=50, beta0=2, beta1=1, sigma=1/2, range=c(.8, 1.2)) |>

Spower(sig.level=.95, sig.direction='above', parallel=TRUE)##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:04:03

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 5

## n beta0 beta1 sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

## 1 50 2 1 0.95 NA

##

## Estimate of power: 0.144

## 95% Confidence Interval: [0.138, 0.151]Finally, to demonstrate why this might be useful, the following estimates the required sample size to achieve 80% power when using a 95% HDI-ROPE criteria.

rope.lm(n=interval(50, 200), beta0=2, beta1=1, sigma=1/2, range=c(.8, 1.2)) |>

Spower(power=.80, sig.level=.95, sig.direction='above', parallel=TRUE)##

## Execution time (H:M:S): 00:14:53

## Design conditions:

##

## # A tibble: 1 × 5

## n beta0 beta1 sig.level power

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 NA 2 1 0.95 0.8

##

## Estimate of n: 107.7

## 95% Predicted Confidence Interval: [106.7, 108.7]